Multiple Hop Patterns and Accumulation

Multiple Hop Pattern Shortest Path Semantics

Repeating the same hop is useful sometimes, but the real power of pattern matching comes from expressing multi-hop patterns, with specific characteristics for each hop. For example, the well-known product recommendation phrase "People who bought this product also bought this other product" is expressed by the following 2-hop pattern:

FROM This_Product:p -(<Bought:b1)- Customer:c -(Bought>:b2)- Product:p2

WHERE p2 != pAs you see, a 2-hop pattern is a simple concatenation and merging of two 1-hop patterns where the two patterns share a common endpoint. Below, Y:y is the connecting end point.

Unnamed Intermediate Vertex Set

A multi-hop pattern has two endpoint vertex sets and one or more intermediate vertex sets. If the query does not need to express any conditions for an intermediate vertex set, then the vertex set can be omitted and the two surrounding edge sets can be joined with a simple .. For example, in the 2-hop pattern example above, if we do not need to specify the type of the intermediate vertex Y, nor need to refer to it in any of the query’s other clauses (such as WHERE or ACCUM), then the pattern can be reduced as follows:

FROM X:x - (E1.E2>) - Z:z|

Note that when we abbreviate that path in this way, we do not support aliases for the edges or intermediate vertices in the abbreviated section. |

Shortest Paths Only for Variable Length Patterns

If a pattern has a Kleene star to repeat an edge, GSQL pattern matching selects only the shortest paths which match the pattern. If we did not apply this restriction, computer science theory tells us that the computation time could be unbounded or extreme (NP = non-polynomial, to be technical). If we instead matched ALL paths regardless of length when a Kleene star is used without an upper bound, there could be an infinite number of matches, if there are loops in the graph. Even without loops or with an upper bound, the number of paths to check grows exponentially with the number of hops.

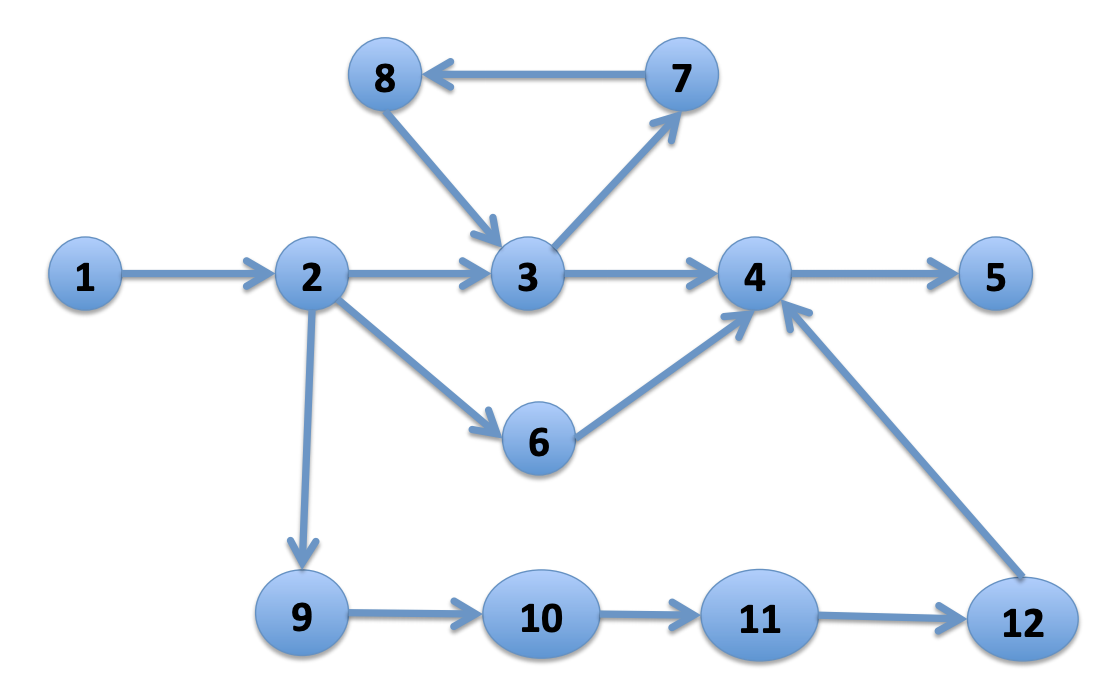

For the pattern 1 - (_*) - 5 in Figure 3 above, you can see the following:

-

There are TWO shortest paths: 1-2-3-4-5 and 1-2-6-4-5

-

These have 4 hops, so we can stop searching after 4 hops. This makes the task tractable.

-

-

If we search for ALL paths which do not repeat any vertices:

-

There are THREE non-repeated-vertex paths: 1-2-3-4-5, 1-2-6-4-5, and 1-2-9-10-11-12-4-5

-

The actual number of matches is small, but the number of paths is theoretically very large.

-

-

If we search for ALL paths which do not repeat any edges:

-

There are FOUR non-repeated-edge paths: 1-2-3-4-5, 1-2-6-4-5, 1-2-9-10-11-12-4-5, and 1-2-3-7-8-3-4-5

-

The actual number of matches is small, but number of paths to consider is NP.

-

-

If we search for ALL paths with no restrictions:

-

There are an infinite number of matches, because we can go around the 3-7-8-3 cycle any number of times.

-

Additional Details about Pattern Matching

Each vertex set or edge set in a pattern (except edges with Kleene stars) can have an alias variable associated with it. When the query runs and finds matches, it associates, or binds, each alias to the matching vertices or edges in the graph.

SELECT Clause

The SELECT clause specifies the output vertex set of a SELECT statement. For a multiple-hop pattern, we can select any vertex alias in the pattern. The example below shows the 4 possible choices for the given pattern:

// select starting end point x

SELECT x

FROM X:x-(E2>:e2)-Y:y-(<E3:e3)-Z:z-(E4:e4)-U:u;

// select y

SELECT y

FROM X:x-(E2>:e2)-Y:y-(<E3:e3)-Z:z-(E4:e4)-U:u;

// select z

SELECT z

FROM X:x-(E2>:e2)-Y:y-(<E3:e3)-Z:z-(E4:e4)-U:u;

// select ending end point u

SELECT u

FROM X:x-(E2>:e2)-Y:y-(<E3:e3)-Z:z-(E4:e4)-U:u;FROM Clause

For a multiple-hop pattern, if you don’t need to refer to the intermediate vertex points, you can just use . to connect the edge patterns, giving a more succinct representation. For example, below we remove y and z, and connect E2>, <E3 and E4 using the period symbol. Note that you cannot have an alias for a multi-hop sequence like E2>.<E3.E4.

// select starting end point x

SELECT x

FROM X:x-(E2>:e2)-Y:y-(<E3:e3)-Z:z-(E4:e4)-U:u;

// if we don't need to access y, z, we can write

SELECT u

FROM X:x-(E2>.<E3.E4)-U:u;WHERE Clause

Each predicate (simple true/false condition) can refer to any of the aliases in the path. As with any database query, more complex conditions may not be as performant as simpler queries with simpler, more local predicate conditions. Consider the pattern and query below:

FROM X1:x1-(E1:e1)-X2:x2-(E2:e2)-X3:x3-(E3:e3)-X4:x4// (x1, e1, x2) belongs to the 1st-hop

// (x2, e2, x3) belongs to the 2nd-hop

// (x3, e3, x4) belongs to the last-hop

// below x1.age > x2.age is a local predicate

// x2.@cnt != x4.@cnt is a cross-hop predicate

// (x1.salary + x3.salary) < x4.salary is a cross-hop predicate

SELECT x

FROM X1:x1-(E1:e1)-X2:x2-(E2:e2)-X3:x3-(E3:e3)-X4:x4

WHERE x1.age>x2.age AND x2.@cnt!=x4.@cnt AND (x1.salary+x3.salary)<x4.salaryPath Patterns as a Regular Expression Language

GSQL’s pattern matching syntax provides the essentials for a regular expression language for paths in graphs. Consider the three basic requirements for a regular expression language:

-

The empty set -→ A path of length zero (no match)

-

Concatenation -→ Combine paths together. You can write an N-hop pattern, and M-hop pattern, and then combine them to have an (N+M)-hop pattern.

-

Alternation (either-or) -→ You can use alternation for both vertex sets and edge sets, e.g.

FROM (Source1 | Source2) -(Edge1> | <Edge 2)- (Target1 | Target2)Note: This is not the same asFROM (Source1 -(Edge1>)- Target 1) | (Source2 -(<Edge2)- Target 2)The latter can be achieved by writing two SELECT query blocks and getting the UNION of their results.

Working with Your Pattern Matches

The point of pattern matching is to identity sets of graph entities that match your input pattern. Once you’ve done that, GSQL enables you to do advanced and efficient computation on that data, from simply counting the matches to advanced algorithms and analytics. This section compares accumulation in the current Pattern Matching syntax to earlier versions.

ACCUM Clause

Just as in classic GSQL syntax, the ACCUM clause is executed once (in parallel) for each set of vertices and edges in the graph which match the pattern and constraints given in the FROM and WHERE clauses. You can think of FROM-WHERE as producing a virtual table. The columns of this matching table are the alias variables from the FROM clause pattern, and the rows are each possible set of vertex and edge aliases (e.g. a path) which fit the pattern.

A simple 1-hop pattern, which could be syntax v1 or v2, looks like this:

FROM Person:A -(IS_LOCATED_IN:B)- City:Cproduces a match table with 3 columns: A, B, and C. Each row is a tuple (A,B,C) where there is a has_lived_in edge B from a Person vertex A to a City vertex C. We say that the match table provides a binding between the pattern aliases and graph’s vertices and edges. A multi-hop pattern simply has more columns than a 1-hop pattern.

|

The |

For example, consider the following clauses:

FROM Person:A -(KNOWS.KNOWS)- Person.C

WHERE C.email = "Andy@www.com"

ACCUM C.@patternCount += 1This finds the friends of the friends of Andy@www.com.

Suppose Andy knows 3 persons (Larry, Moe, and Curly) who know Wendy.

The accumulator C.@patternCount will be incremented 3 times for C = Wendy.

This is similar to a SQL SELECT C, COUNT(*) ... GROUP BY C query.

There is no alias for the vertex in the middle of KNOWS.KNOWS so the identities of Larry, Moe, and Curly cannot be reported.

POST-ACCUM Clause

At the end of the ACCUM clause, all the requested accumulation (+=) operators are processed in bulk, and the updated values are now visible.

You can now use POST-ACCUM clauses to perform a second, different round of computation on the results of your pattern matching.

The ACCUM clause executes for each full path that matches the pattern in the FROM clause.

In contrast, the POST-ACCUM clause executes for each vertex in one vertex set (e.g. one vertex column in the matching table); its statements can access the aggregated accumulator result computed in the ACCUM clause.

If you want to perform per-vertex updates for more than one vertex alias, you should use a separate POST-ACCUM clause for each vertex alias.

The multiple POST-ACCUM clauses are processed in parallel; it doesn’t matter in what order you write them.

(For each binding, the statements within a clause are executed in order.)

For example, below we have two POST-ACCUM clauses.

The first one iterates through s, and for each s, we do s.@cnt2 += s.@cnt1.

The second POST-ACCUM iterations through t.

USE GRAPH ldbc_snb

INTERPRET QUERY () SYNTAX v2 {

SumAccum<int> @cnt1;

SumAccum<int> @cnt2;

R = SELECT s

FROM Person:s-(Likes>) -:msg - (Has_Creator>)-Person:t

WHERE s.first_name == "Viktor" AND s.last_name == "Akhiezer"

AND t.last_name LIKE "S%" AND year(msg.creation_date) == 2012

ACCUM s.@cnt1 +=1 //execute this per match of the FROM pattern.

POST-ACCUM s.@cnt2 += s.@cnt1 //execute once per s.

POST-ACCUM t.@cnt2 +=1;//execute once per t

PRINT R [R.first_name, R.last_name, R.@cnt1, R.@cnt2];

}which produces the result

{

"error": false,

"message": "",

"version": {

"schema": 0,

"edition": "enterprise",

"api": "v2"

},

"results": [{"R": [{

"v_id": "28587302323577",

"attributes": {

"R.first_name": "Viktor",

"R.last_name": "Akhiezer",

"R.@cnt1": 3,

"R.@cnt2": 3

},

"v_type": "Person"

}]}]

}However, the following is not allowed, since it involves two aliases (t and s) in one POST-ACCUM clause.

POST-ACCUM t.@cnt1 += 1,

s.@cnt1 += 1Also, you may not use more than one alias in a single assignment. The following is not allowed:

POST-ACCUM t.@cnt1 += s.@cnt + 1Examples of Multiple Hop Pattern Match

You can copy any of the shown GSQL scripts to a file with the file extension .gsql and invoke it in a Linux shell to see the results.

gsql example.gsqlExample 1

Find the 3rd superclass of the Tag class whose name is "TennisPlayer".

USE GRAPH ldbc_snb

INTERPRET QUERY () SYNTAX v2 {

Tag_Class1 =

SELECT t

FROM Tag_Class:s-(Is_Subclass_Of>.Is_Subclass_Of>.Is_Subclass_Of>)-Tag_Class:t

WHERE s.name == "TennisPlayer";

PRINT Tag_Class1;

}{

"error": false,

"message": "",

"version": {

"schema": 0,

"edition": "enterprise",

"api": "v2"

},

"results": [{"Tag_Class1": [{

"v_id": "239",

"attributes": {

"name": "Agent",

"id": 239,

"url": "http://dbpedia.org/ontology/Agent"

},

"v_type": "Tag_Class"

}]}]

}Example 2

Find in which continents were the 3 most recent messages in Jan 2011 created.

USE GRAPH ldbc_snb

INTERPRET QUERY () SYNTAX v2{

SumAccum<String> @continent_name;

acc_msg_continent =

SELECT s

FROM (Comment|Post):s-(Is_Located_In>.Is_Part_Of>)-Continent:t

WHERE year(s.creation_date) == 2011 AND month(s.creation_date) == 1

ACCUM s.@continent_name = t.name

ORDER BY s.creation_date DESC

LIMIT 3;

PRINT acc_msg_continent;

}{

"error": false,

"message": "",

"version": {

"schema": 0,

"edition": "enterprise",

"api": "v2"

},

"results": [{"acc_msg_continent": [

{

"v_id": "824634837528",

"attributes": {

"browser_used": "Internet Explorer",

"@continent_name": "Asia",

"length": 115,

"image_file": "",

"location_ip": "87.251.6.121",

"id": 824634837528,

"creation_date": "2011-01-31 23:58:03",

"lang": "tk",

"content": "About Adolf Hitler, iews. His writings and methods were often adapted to need and circumstance, although there were"

},

"v_type": "Post"

},

{

"v_id": "824636727408",

"attributes": {

"browser_used": "Firefox",

"@continent_name": "Europe",

"length": 3,

"location_ip": "31.2.225.17",

"id": 824636727408,

"creation_date": "2011-01-31 23:57:46",

"content": "thx"

},

"v_type": "Comment"

},

{

"v_id": "824640012997",

"attributes": {

"browser_used": "Firefox",

"@continent_name": "Asia",

"length": 7,

"location_ip": "27.112.21.246",

"id": 824640012997,

"creation_date": "2011-01-31 23:54:28",

"content": "no way!"

},

"v_type": "Comment"

}

]}]

}Example 3

Find Viktor Akhiezer’s favorite author of 2012 whose last name begins with the letter 'S'. Also find how many LIKES Viktor has given to the author’s post or comment.

USE GRAPH ldbc_snb

INTERPRET QUERY () SYNTAX v2{

SumAccum<int> @likes_cnt;

favorite_authors =

SELECT t

FROM Person:s-(Likes>) -:msg - (Has_Creator>)-Person:t

WHERE s.first_name == "Viktor" AND s.last_name == "Akhiezer"

AND t.last_name LIKE "S%" AND year(msg.creation_date) == 2012

ACCUM t.@likes_cnt +=1;

PRINT favorite_authors[favorite_authors.first_name, favorite_authors.last_name, favorite_authors.@likes_cnt];

}{

"error": false,

"message": "",

"version": {

"schema": 0,

"edition": "enterprise",

"api": "v2"

},

"results": [{"favorite_authors": [

{

"v_id": "8796093025410",

"attributes": {

"favorite_authors.last_name": "Singh",

"favorite_authors.@likes_cnt": 1,

"favorite_authors.first_name": "Priyanka"

},

"v_type": "Person"

},

{

"v_id": "2199023260091",

"attributes": {

"favorite_authors.last_name": "Seppala",

"favorite_authors.@likes_cnt": 1,

"favorite_authors.first_name": "Janne"

},

"v_type": "Person"

},

{

"v_id": "15393162796846",

"attributes": {

"favorite_authors.last_name": "Santos",

"favorite_authors.@likes_cnt": 1,

"favorite_authors.first_name": "Mario"

},

"v_type": "Person"

}

]}]

}Multi-Block Queries

We have shown how complex multi-hop patterns, containing even a conjunctive of patterns, can be expressed in a single FROM clause of a single SELECT query. There are times, however, when it is better or necessary to write a query with more than one SELECT block. This could be because of the need to do computation and decision matching in stages, to make the query easier to read, or to optimize performance.

Regardless of the reason, GSQL has always supported writing procedural queries containing multiple SELECT query blocks. Moreover, each SELECT statement outputs a vertex set. This vertex set can be used in the FROM clause of a subsequent SELECT block.

For example, if Set1, Set2, and Set3 were the outputs of three previous SELECT blocks in this query, then each of these FROM clauses can take place later in the query:

-

FROM Set1:x1 -(mh1)- :x2 -(mh2)- Set3:x3 -

FROM :x1 -(mh1)- :x2 -(mh2)- Set3:x3 -

FROM Set2:x1 -(mh1)- :x2 -(mh2)- Set2:x3

Example 1

Find Viktor Akhiezer’s liked messages whose authors' last names begin with S. Find these authors' alumni count.

USE GRAPH ldbc_snb

// a computed vertex set F is used to constrain the second pattern.

INTERPRET QUERY () SYNTAX v2 {

SumAccum<int> @@cnt;

F = SELECT t

FROM :s -(Likes>:e1)- :msg -(Has_Creator>)- :t

WHERE s.first_name == "Viktor" AND s.last_name == "Akhiezer" AND t.last_name LIKE "S%";

Alumni = SELECT p

FROM Person:p -(Study_At>) -:u - (<Study_At)- F:s

WHERE s != p

Per (p)

POST-ACCUM @@cnt+=1;

PRINT @@cnt;

}

// results

{

"error": false,

"message": "",

"version": {

"schema": 0,

"edition": "enterprise",

"api": "v2"

},

"results": [{"@@cnt": 223}]

}Example 2

Find Viktor Akhiezer’s liked posts' authors A, and his liked comments' authors B. Count the universities that members from groups A and B studied at.

USE GRAPH ldbc_snb

// A and B are used to constrain the third pattern.

INTERPRET QUERY () SYNTAX v2 {

SumAccum<int> @@cnt;

A = SELECT t

FROM :s -(Likes>:e1)- Post:msg -(Has_Creator>)- :t

WHERE s.first_name == "Viktor" AND s.last_name == "Akhiezer" ;

B = SELECT t

FROM :s -(Likes>:e1)- Comment:msg -(Has_Creator>)- :t

WHERE s.first_name == "Viktor" AND s.last_name == "Akhiezer" ;

Univ = SELECT u

FROM A:p -(Study_At>) -:u - (<Study_At)- B:s

WHERE s != p

Per (u)

POST-ACCUM @@cnt+=1;

PRINT @@cnt;

}

// results

{

"error": false,

"message": "",

"version": {

"schema": 0,

"edition": "enterprise",

"api": "v2"

},

"results": [{"@@cnt": 4}]

}Example 3. Find Viktor Akhiezer’s liked posts' authors A. See how many pairs of persons exist in A such that one person likes a message authored by another person.

USE GRAPH ldbc_snb

// a computed vertex set A is used twice in the second pattern.

INTERPRET QUERY () SYNTAX v2 {

SumAccum<int> @@cnt;

A = SELECT t

FROM :s -(Likes>:e1)- Post:msg -(Has_Creator>)- :t

WHERE s.first_name == "Viktor" AND s.last_name == "Akhiezer" ;

A = SELECT p

FROM A:p -(Likes>) -:msg - (Has_Creator>) - A:p2

WHERE p2 != p

Per (p, p2)

ACCUM @@cnt +=1;

PRINT @@cnt;

}

// results

{

"error": false,

"message": "",

"version": {

"schema": 0,

"edition": "enterprise",

"api": "v2"

},

"results": [{"@@cnt": 8341}]

}Example 4

Find how many messages are created and liked by the same person whose first name begins with the letter T.

USE GRAPH ldbc_snb

// the same alias is used twice in a pattern

INTERPRET QUERY () SYNTAX v2 {

SumAccum<int> @@cnt;

A = SELECT msg

FROM :s -(Likes>:e1)- :msg -(Has_Creator>)- :s

WHERE s.first_name LIKE "T%"

PER (msg)

ACCUM @@cnt +=1;

PRINT @@cnt;

}

// results

{

"error": false,

"message": "",

"version": {

"schema": 0,

"edition": "enterprise",

"api": "v2"

},

"results": [{"@@cnt": 207}]

}

// to further verify, we picked one message from the above query result.

// see if there exists a person who likes her own message.

INTERPRET QUERY () SYNTAX v2 {

R = SELECT s

FROM :msg -(Has_Creator>)- :s

WHERE msg.id == 1374390714042;

T = SELECT s

FROM R:s -(Likes>)- :msg

WHERE msg.id == 1374390714042;

PRINT R;

PRINT T;

}

// results

{

"error": false,

"message": "",

"version": {

"schema": 0,

"edition": "enterprise",

"api": "v2"

},

"results": [

{"R": [{

"v_id": "13194139533433",

"attributes": {

"birthday": "1985-11-26 00:00:00",

"browser_used": "Internet Explorer",

"gender": "female",

"speaks": [

"uk",

"ro",

"en"

],

"last_name": "Kofler",

"location_ip": "31.131.28.133",

"id": 13194139533433,

"creation_date": "2011-01-29 01:14:27",

"first_name": "Taras",

"email": [

"Taras13194139533433@gmail.com",

"Taras13194139533433@yahoo.com"

]

},

"v_type": "Person"

}]},

{"T": [{

"v_id": "13194139533433",

"attributes": {

"birthday": "1985-11-26 00:00:00",

"browser_used": "Internet Explorer",

"gender": "female",

"speaks": [

"uk",

"ro",

"en"

],

"last_name": "Kofler",

"location_ip": "31.131.28.133",

"id": 13194139533433,

"creation_date": "2011-01-29 01:14:27",

"first_name": "Taras",

"email": [

"Taras13194139533433@gmail.com",

"Taras13194139533433@yahoo.com"

]

},

"v_type": "Person"

}]}

]

}